I’m picking up and moving Learning Journal to a new home, integrated with my personal web site, Learning 4 Learning Professionals. Please follow me there; it will be lonely without you! New URL: http://l4lp.com/blog/

Sometimes, random dots create interesting pictures. Over the weekend, my disparate reading ventures raised some points that when connected together formed a nuanced line of thought around how to approach my role in supporting professional development for folks in the L&D field.

Dot 1: I read a lovely novel by Jodi Picoult, called Leaving Time, which included a great deal of information about elephant behavior. (Stay with me, there is a relevant point here…) Elephants “allomother” their young; the elephants in a herd, especially female siblings, all do their part to raise babies. They are for the most part endlessly patient in doing so, gently redirecting behavior and teaching the skills needed to thrive in the wild. Allomothers provide good role-modeling, give youngsters freedom to explore, set limits as needed, and staunchly defend their young from predators that might injure them. It’s always dangerous to anthropomorphize, but the behavior described reads like deep love and concern, a deliberate and gentle way of facilitating learning in a world that can be harsh.

Dot 2: I came across some articles and blog posts that were discussing the challenges of political correctness.* A key point from these pieces is that some of our critique of one another – pointing out offensive word choices and calling out people for taking opposing stands on hot-topic issues – is not conducive to our ability to educate one another. These days, conversations, especially online, can be strident and accusatory, and social media often exacerbates the sense of piling on when someone’s opinions are out of line with group views. There is too often little tolerance for making inadvertent mistakes (in language use, in interpretation), and little room given for opening a discussion and listening to varied perspectives. And yet we know that some of the most significant learning and education requires deep listening, questioning one’s own assumptions, and building from common ground. I have seen clear evidence of the kind of politically-charged conversations that were referenced in the articles, and I have also seen echoes of this same sort of back-and-forth in the blogs and Twitter feeds in our own field.

Dot 3: Because I’m teaching three online courses at the moment, I spent a number of hours reading discussion posts, mostly on the subject of learning and development strategies in organizations. As usually happens in this context, students’ comments provide opportunity to clarify theory and research on hot-button topics like learning styles, generational differences, proper phrasing of learning objectives, and the like. At varying times, I found myself torn between:

- wanting to be absolutely certain students adopt the “right” beliefs and practices (Read: my beliefs and practices),

- wanting to understand where these odd ideas come from and why they persist (Am I missing something? Do they know something I don’t?), and

- wanting to warn my students that some of their statements could get them eviscerated by others in the field who disagree.

When I connect those dots, I wonder if maybe allomothering (gently guiding) and asking deeper questions (not forcing students to be “p.c.”) is a much better way of shaping professional behavior than playing the professor/expert trump card and telling students and fellow professionals what to believe and how to do their work.

I realize that to some degree, people want to have experts (managers, professors, thought leaders) tell them what to do. And there is often overwhelming evidence and agreement that allows us to provide unequivocal recommendations. Like the allomothers, we may indeed know what is best. But that does not mean that we should come down hard on those who see things differently. If we act like p.c. police, we run the risk of alienating the very people we want to bring over to our points of view. We can’t educate if we don’t first seek to understand others’ perspectives. Making people feel small (with a condescending pronouncement or a low grade) isn’t the best way to persuade.

And there’s another reason to be cautious about our surety. Some debates are still bubbling. Sometimes we turn out to be wrong. Science uncovers new findings. The nature of the world changes. Newer techniques replace the old. There has to be room for us to talk with one another – to really question one another – or we will never hear the voices of those on the cutting edge leading us to new territory.

As I think about my own work, there are many times when I hear statements that stem from what I view as inaccurate interpretations of theory and research, surface understanding of key ideas, or belief in debunked or outmoded theories and models. When that happens, there are a couple of ways I can go as a teacher / coach / facilitator. I can take a strong stand: “I’m the expert, and this is the right model.” Or I can play the co-learner: “Here’s my understanding of the issue and my reasoning; here’s some additional research or readings for you to consider; tell me what you think and let’s discuss.” The latter approach communicates respect, allows for robust debate, provides opportunities to persuade, and has a much better potential for deeply impacting a developing professional’s theory and practice. And if I really listen to their responses, it also allows for the possibility that students and new professionals have something to teach me.

* My crash course in the consequences of political correctness all started with an NPR report that drew my attention here, and then I followed links here, here, and here before I really needed to get on with my day.)

Posted in Article Discussions, Reflections | Leave a Comment »

This post is inspired by a profound essay from Mike Caulfield called Design Patterns and the Coming Revolution in Course Design. It’s the text of his keynote address at the Northwest eLearning conference earlier this week. While Mike’s examples come from the arena of academic course design, instructional designers and learning consultants in the corporate world will recognize the issues and relate to the recommendations. I urge you read Mike’s post before continuing with this one. Get a cup of coffee first; it’s a long one – but worth every word.

Thanks for coming back… here’s why I’m so excited about Mike’s propositions:

The need for a pattern book

I am sometimes bothered by the way we can block-copy design ideas from one context to another, resulting in same-same course designs that lose something in the translation. Since I am educated in adult learning theory and research, I have always recommended that designers get solid grounding in the theory and research around how learning works so that they can make more informed decisions about design. I can see, though, that documenting design patterns and using these as guideposts for course design is a fabulous idea.

Patterns translate key principles from adult learning into clear recommendations. Folks like Julie Dirksen, Karl Kapp, Michael Allen, and Ruth Clark (references below) have done some of this translation work for people in L&D, but I don’t think they quite constitute design patterns as Mike describes them. I’ll have to check out the book that Mike mentions,Technology-Enhanced Learning: Design Patterns and Pattern Languages, edited by Goodyear and Retalis.

We need a design pattern book for our work. I’ve no idea how to create that, but I’ll be noodling on it for quite a while. As I think about it, it feels like a herculean task. There may be too many if-then’s (or when… therefore…’s) that form the foundation of design. And if you do create a pattern book, would it be too big to be really useful? You’d have to categorize the patterns, I think. But I bet it would be more useful than reading and trying to apply a textbook on learning theory. (Don’t tell my adult learning students I said that.)

The design process

Another aspect of Mike’s post that resonated with me was the analogy between course design and music composition. He says, “When you work solo on multi-track, as I do, and you are scoring 5 to 20 instruments you become acutely aware that each decision you make constrains you further. As you progress, there really are limited ways these things can fit together.”

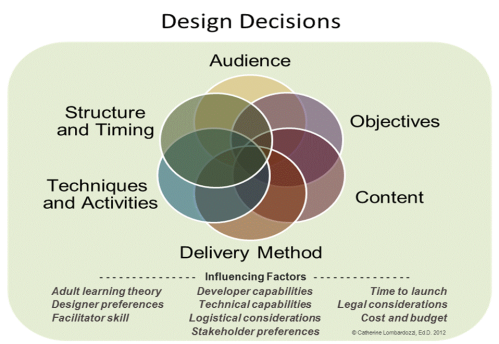

I have come to the point where I describe design as a set of decisions (audience, objectives, content, delivery method, activities, and structure). These decisions can’t be made in a linear fashion because each decision imposes constraints and opportunities for the other decisions. There are many different ways to finalize the decisions that will work, and some that simply won’t work. The music analogy is truly applicable. While you are composing/designing, you constantly adjust your decisions to ensure they continue to blend together as a whole. There are limited ways these things fit together, but there are multiple ways that would produce a pleasing piece.

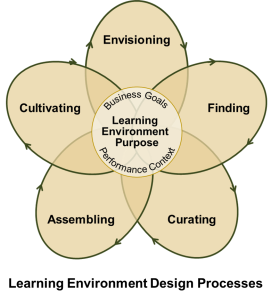

This insight is timely because next week, I’m working on the design process section of my Learning Environments by Design book. Designing a learning environment isn’t as constrained as designing a course – it’s a much more emergent, ongoing process. I want to be sure I communicate that eve though you might need a vision to launch an environment, it will morph and change over time – perhaps more like an improvised jazz piece.

Thanks to Mike, then, I’ll have lots to think about – as I am designing courses and learning environments – and as I am helping others to develop their design skills. Comments welcome!

Books referenced above: Julie Dirkson’s Design for How People Learn, Karl Kapp’s The Gamification of Learning and Instruction, Michael Allen’s Designing Successful e-Learning, and Ruth Clark’s e-Learning and the Science of Instruction.

Posted in Instructional Design / ADDIE, Learning Environment Design | 6 Comments »

As I continue to work on a book on learning environment design, I can’t help but see relevant ideas everywhere I look. As part of a current cMOOC on Connected Courses, I was reintroduced to theory and research around connected and open learning. Although the conversation in Connected Courses is most often about how design more open and enriching learning experiences in the academic environment (K-12 and Higher Ed), the features of connected learning and many of the recommendations from research in that arena have resonated with some of my own writing and advice on learning environment design.

Connected learning “advocates for broadened access to learning that is socially embedded, interest driven, and oriented toward educational, economic or political opportunity. Connected learning is realized when a young person is able to pursue a personal interest or passion with the support of friends and caring adults, and is turn able to link this learning and interest to academic achievement, career success, or civic engagement.” (Ito et al, reference below.)

Change a few words around, and we can apply the concept of connected learning to workplace learning as well – ensuring that it is socially embedded, interest-driven, and oriented toward achievement (performance, skill development). It requires a commitment to learning and a network of supportive colleagues.

In their 2013 report on Connected Learning, Mizuko Ito and her coauthors suggest four design principles for connected learning: open access, learning by doing, challenge, and interconnectivity. These principles provide terrific quality markers for learning environments as well. (For more, see p. 81 of the report)

Given these design principles, here are some of the questions I might ask when designing a learning environment:

Open participation:

ease of access, multiple ways to participate, multiple levels of expertise in community, recognition for support for each other’s learning

- How can we make participation inviting and allow people with different communication preferences and levels of interest to effectively engage with the group as needed?

- How can we open up the learning environment so that learners have access to people and ideas that are different enough to provoke innovation?

- How do we make sharing easy and encourage reciprocation?

We know that building social engagement among learners who don’t have a history together can be tricky business. It’s important to do what we can to make it easy for learners to engage with one another and with experts within and outside of the organization. There is a lot of additional material on building communities that has also proven helpful in meeting this design principle.

Learning by doing:

authentic and relevant engagement in the work, access to experts and mentors who can mitigate risk, abundant resources for learning in the flow of work

- How can we support learning by doing – make it safe to experiment and support the development of new practices?

- What tools can support learning by doing?

- How can we make job aids and other supports more readily available as needed?

Doing the work is often the most fertile ground for learning IF people attend to what they are learning and take advantage of opportunities for learning that are embedded in everyday projects. Having a culture of learning that provides just-in-time resources and lots of social support makes a difference in terms of how much people learn in the work. We also need to recognize and celebrate that learning.

Challenge:

scaffolding learning, sharing within a context that supports constructive feedback

- How do we ensure that learners are sufficiently challenged in the work environment to develop the knowledge and skills needed?

- How do we scaffold the harder aspects of learning and ensure people are supported through any stumbles they might make along the way?

- How can we enable constructive feedback processes and collaboration for joint learning?

There are some who say that problem-solving and failure are at the root of all learning. While I don’t believe that, I certainly endorse the idea that work challenges provide great opportunity for learning – many people will tell you that the projects they struggled with are some of the most developmental. But work challenges can also just be a bane on our existence; how do we ensure that challenges are positive learning experiences and not just ordeals to get through?

Interconnectivity:

alignment of multiple paths for learning, easy sharing between platforms

- How do we ensure that all of the components that support learning are aligned so as not to confuse with conflicting advice or goals?

- How do we bring diverse supportive tools together for ease of access?

- How do we help people leverage one another’s work to advance practice as a whole?

- How do we connect to the “outside” world to bring in ideas and expertise that would be helpful?

This criteria harkens back to the idea of a learning ecosystem; the tools we use for sharing, working, and communicating need to be in synergy with one another if they are to be useful. And it isn’t just systems that can be interconnected; we can also advocate for and strengthen learner’s ability to connect with people and ideas outside of their normal flow of work. These infusions of new perspectives can be a real boon to learning. (Just like taking Connected Courses has helped me in expanding my ideas on learning environment design.)

If these ideas resonate with you, you may be interested in joining the Connected Courses conversation. If you’d like to learn more about learning environment design, please join me for my Guild Academy course, Learning Ecosystems: Designing environments for learning – it launches again on October 15. In it, you’ll have the opportunity to connect with others who are working on these kinds of strategies and get advice and feedback on your own work.

Source: Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. (2013) By Mizuko Ito, Kris Gutiérrez, Sonia Livingstone, Bill Penuel, Jean Rhodes, Katie Salen, Juliet Schor, Julian Sefton-Green, and S. Craig Watkins. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Posted in Learning Environment Design | Leave a Comment »

Beginning next week, I am participating in a collaborative online event called Connected Courses. It is a cMOOC organized to discuss practices on creating effective open online learning. I’ll be posting to my new Out Loud Learning blog, and you can follow along there if you like.

If you teach online, design corporate MOOCs, or are interested in open learning – you might want to join the Connected Courses community as well. We need to do more cross-discussion between corporate L&D practices and academic practices for learning facilitation. I’ll be keeping one foot in each of those two practice areas for the duration of the course myself.

This post is a copy of my initial post for Connected Courses.

Not ready, get set.

We have something of a dilemma in the learning and development world these days. On the one hand, the vast resources of the internet, the reach of social media, and the availability of videos, webinars, free courses, and MOOCs make learning easy to access. On the other hand, many people have neither the time nor the learning skills to pursue the learning they really need. They simply aren’t ready to take advantage of new tools and strategies for learning.

Whether in the corporate L&D space or in the academic world, there are challenges to changing our strategies for facilitating learning. Open, self-directed learning can be hard. Learners have to find helpful resources, which can be a daunting task with the world wide web as a database. Even when we curate the resources, many people are not accustomed to facilitating and processing their own learning activities.

We’ll get better at all this, I am sure, but in the meantime, we need to scaffold open, self-directed learning. I am convinced that there is more that we can do as designers of learning activities to help people get set up for success in the world of open learning.

That’s what is prompting me to join the Connected Courses active co-learning course over the next few months. I am looking forward to learning from and with all the folks who are joining in. I recognize some of the participants as people on the leading edge in developing open learning strategies, and I’m seeing posts from fellow participants who are thoughtful explorers like me.

To introduce myself, I am a consultant to folks who work in corporate L&D and a faculty member teaching designers, human resource development specialists, and learning technology folks. I design and teach courses for those who design and teach and consult on learning strategies. I am also actively promoting a learning environment design framework that I believe can help us to set learners up for success, even when they’re not quite ready to manage their own ongoing development. So learning more about connected learning is a priority for me. (More About me)

I am not immune to the challenges of participating in a loose “course” like this one. Like many, I have started and not fully engaged in a variety of open learning offerings, so I know that unless I have some pressing goals for staying on top of the conversation, this, too, will get buried by other priorities. (Self-directed leaning 101) To begin, then…

My goals for Connected Courses (not in any particular order):

- Observe facilitation and learning in the course and leverage strategies that might work in the environments for which I design learning.

- Deepen understanding of underpinning strategies and theory to better discern what is essential (and not essential) and how to customize approaches effectively.

- Connect to people whose ongoing work I find interesting (and who may be interested in my work).

- Curate resources useful in the context of courses and topics I currently facilitate.

- Strengthen my skills in engaging in connected learning in an open learning context.

- Actively apply what I’m learning in Connected Courses to the redesign of my e-collaboration course for January 2015.

So I’m in. I’m gearing up and scheduling time to engage. I look forward to working with you all.

Get ready, get set.

Posted in To Learn List, Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Every once in a while you read a book that smacks you in the head with inspiration and ideas that can seem so clear, but are also hard to firmly grasp. Creativity Inc, by Ed Catmull (with Amy Wallace), is one such book. If you lead creative people or work in a creative field, it should definitely be at the top of your reading list.

The book is full of interesting stories and important lessons, and you’ll get a real inside view of Pixar and the decisions and accidents that led to its amazing success. But more importantly, you’ll get a terrific how-to manual for managing creative teams.

For me, Catmull’s reflection gave clear voice to some of my own emerging philosophy, helped clarify things that have been nagging me, and occasionally laid bare wrongheadedness that I had not yet seen. My copy is full of highlighted sections and scribbled margin notes, and I looked forward to writing this post so I could process just a few of them into articulate insights. I’m hoping my reflections here might start a cyber conversation among other L&D people who have read the book.

Here are just three major take-aways from my perspective.

The importance of cultivating true collaboration

Catmull shared three related ideas: First, greatness is born of collaboration. And real collaboration is evidenced by the day-to-day behaviors of teams that work together, not occasional events. Most importantly, candid critique is a critical component of healthy collaboration, so we need to work hard to ensure people can effectively give and receive feedback.

Here’s Ed Catmull on the subject:

“Too many of us think of ideas as being singular, as if they float on the ether, fully formed and independent of the people who wrestle with them. Ideas, though, are not singular. They are forged through tens of thousands of decisions, often made by dozens of people.” (p. 75)

“Getting the team right is the necessary precursor to getting the ideas right. It is easy to say you want talented people, and you do, but the way those people interact with one another is the real key.” (p.74)

“A hallmark of a healthy creative culture is that its people feel free to share ideas, opinions, and criticisms.” (p. 86)

What strikes me when looking at L&D processes and cultures is that don’t often imagine processes that allow for creative ideas to emerge from good tries and critiques.

We sometimes don’t even imagine processes that rely on collaboration, but instead assign projects to individual designers and developers. There is real magic in collaboration, as Pixar’s success can attest. Since I now have a one-person consulting practice, I am very jealous of people who are surrounded by other talented L&D colleagues with whom they can easily collaborate – and I am sad to realize that we don’t actually take advantage of that very often. I know I have to find more collaborators myself, and “working out loud” can make a difference.

We have to find more ways to draw on the talents of our teams to work together toward an outcome rather than working serially to just do their part. We have to be open to hearing critique of our work and be willing to share candid feedback with our peers, and that can be hard.

The good news is that the agile* and successive approximation** design processes that seem to be coming to the fore in our field are more amenable to a collaborative process. We need to be careful that we don’t eliminate the collaborative features of these processes when we implement those design models.

The need to trust the people, not the process.

“We should trust in people, I told them, not processes. The error we’d made was forgetting that “the process” has no agenda and doesn’t have taste. It is just a tool – a framework.” (p. 79)

So true! “The process” can’t tell good work from bad! Our people, on the other hand, are often very astute at sensing or judging what works.

Catmull talks quite a bit about how important it is to trust creative people to do what they do. We can give parameters and get out of the way, and many creative people will be able to work within limits. It strikes me that too many creative teams in L&D are locked down by process, artificial deadlines, and defined roles and responsibilities.

“Making the process better, easier, and cheaper is an important aspiration, something we continually work on – but it is not the goal. Making something great is the goal.” (p. 134)

L&D has a love-hate relationship with process, I think. We have dozens of models that sketch out the steps that result in instructional products, performance support products, and other outcomes. Many organizations have worked hard to improve process efficiency. But the truth is that our process emerges with the needs of individual projects, outcomes, and clients. I used to joke that we needed to date-stamp our process maps, because they needed to be adjusted so often to account for changing circumstances and new recommendations for improvement.

It’s the people we should trust will get the job done, not the process.

Catmull describes processes that actually allow for (and encourage if needed) a complete re-envisioning of the project – including the entire premise and the flow of the story from which Pixar movies are developed.

Nailing down the outcome too soon is a mistake – creative ideas need room to iterate and find their footing. We think that we can sketch a design immediately after assessment, and that design can be solidified for approval before we begin development. But maybe we shouldn’t push so hard for that flow.

I admit that I have been one who has insisted on final objectives and fleshed out designs before development begins – and that idea sounds smart. It’s now quite clear to me that isn’t how it works. We can agree on initial design ideas, but we have to have room to iterate, change our minds, get brilliant ideas, while we are in the process of developing. And collaboration and candid critiques are important parts of that process.

Pixar has the advantage of working on a closed set while ideas get massaged into shape. We have clients that need to be involved, and a loose creative processes can look pretty messy to them. But Michael Allen’s successive approximation method and others like it demonstrate that there are ways to have clients be completely engaged in an iterative process and still be more than satisfied with the outcome.

How to manage with humility

“I’ve spent nearly forty years thinking about how to help smart, ambitious people work effectively with one another. the way I see it, my job as a manager is to create a fertile environment, keep it healthy, and watch for the things that undermine it.” (p. xv)

Aside from being a terrific how-to manual for managing creative work groups and processes, Creativity, Inc. is a book-length reflection by a senior leader describing his process of growth as a manager – a process that includes significant self-monitoring, deliberate reflection, peer discussion, and planned action. It’s about how to be a humble and thoughtful leader – how to focus relentlessly on one’s self, on what “I” can do to be better rather than on pointing out the flaws in processes, people, and outcomes. Ed Catmull has acted quite generously in letting us into his mind and his meditations on creativity, leadership, and leading creative people.

I love his commitment to leaders as teachers:

“Are we thoughtful about how people learn and grow? As leaders, we should think of ourselves as teachers and try to create companies in which teaching is seen as a valued way to contribute to the success of the whole. Do we think of most activities as teaching opportunities and experiences as ways of learning? One of the most crucial responsibilities of leadership is creating a culture that rewards those who lift not just our stock prices but our aspirations as well.” (p. 123)

I no longer have the privilege of leading others in my day-to-day work, but I am often working with learning professionals who see me as an experienced practitioner and potential mentor. I love my generative role as learning facilitator for learning professionals. I recognize that my job is not to tell others what to do and how to do it, but to facilitate an ongoing conversation about how past successes and current innovations can be leveraged for what’s next in L&D. I don’t see my role as consultant and professor as me teaching “them” – my approach is much more facilitative. Catmull gave me a great deal to consider about how to create a positive culture for learning in the engagements I pursue.

At the very beginning of the book, Ed Catmull says that Creativity, Inc. “is an expression of the ideas that I believe make the best in us possible” (p. xvi). The book helps us understand how to bolster creativity, aspire to excellence, and create a successful, profitable business through great results. there are many more gems than what I tried to capture here, some very personal to my own work and experience; I an sure you will find the same. Highly recommended.

But wear headgear because it might smack you on the head, too.

Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration. By Ed Catmull with Amy Wallace. (Random House, 2014)

* For more on Agile methodology, look here.

** For more on the successive approximation method, go here.

Posted in Book Discussions | 3 Comments »

Journal articles and blog posts related to L&D seem fairly uniform in their advice that L&D departments should find non-training ways to support learning. Here’s some of what we’re hearing: use the power of social learning; show your work; give performance support; leverage internet resources; design “courses” only as a last resort.

All of this is good advice, but workable only if underlying assumptions are true. And one of the underlying assumptions here is that people are ready to engage with these kinds of learning strategies if we will just get out of the way. Some people surely are. But many are not, and they need something more from us.

Ryan Tracey, in a blog post a few months ago, called out this “inconvenient truth” by saying, “they are not like us.” His point was that we know from our experience that many employees do not participate in these new venues; they are not exporing MOOCs, building a network on Twitter, or developing their internet search skills. Many don’t have the time or inclination; some prefer formal training; but many more are just not quite sure how to engage this way.

The 2014 learning culture study* from the Corporate Executive Board’s Learning & Development arm underscores the issue with the provocative finding that only 20% of employees are effective learners. So just getting employees to participate in new venues isn’t enough; we need to help them engage effectively.

CEB recommends that learning leaders focus on creating a productive learning culture, and their advice dovetails quite nicely with the learning environment design framework that I have been advocating. Among their conclusions, CEB researchers suggest that L&D should focus on narrowing the resources available to the most relevant few (curate), building learning capability, and promoting a supportive environment in which people share and help one another to learn.

L&D professionals too often feel on the sidelines when it comes to fostering a learning culture. “Culture” is a tough nut to crack, strongly influenced by long history and difficult to counter if a shift in culture is needed.

But I would submit that designers and learning leaders already have in their skill sets the raw tools needed to build the learning capability necessary for a strong learning culture. The key is to turn our talents taward quietly helping people in our organizations to learn new ways to learn – to develop personal learning habits that may not have been a part of their education or learning strategies to this point.

Here are six tools we can turn to the task of developing leanring culture:

Curation – Studies have shown that too much choice often leads to frustration and decision paralysis. We can help to point out the best resources for our learners.

Contextualization – If the relevance and usefulness of resources isn’t obvious, we can help to show the way by providing additional background and advice along with links.

Relationship-building – We can work to ensure that formal training efforts build employees’ developmental networks at the same time. Helping learners to connect with experts, with like-minded peers, and with others who can support their growth and development is one of those gifts that keeps on giving.

Scaffolding – We can help people learn to use tools by scaffolding the learning process both within formal events and beyond. We’ve been doing this with blended solutions for years; we can take it to the next level by consistently walking people through a learning process that includes accessing resources, learning, reflection, practice, feedback, and more.

Mapping – Even with good curation, learners often need a lttle guidance in organizing a developmental plan. We can apply our skill at sequencing to give simple direction on which resouces and activities to tackle first and how to effectively build knowledge and skill over time.

Assembling – As a final contribution, we can make resources and activities accessible in a visually pleasing and intuitively useful portal. That way, employees aren’t spending so much time wading through a mess of links and files.

Lest you think that your design skills will be going to waste in 21st century learning cultures, rest assured that they are more valuable than ever. In our history as a field of practice, L&D professionals have learned quite a bit about how to support learning, and this knowledge can be applied to support our learners in new ways.

If you find these ideas intriguing, you may be interested in reading more about Learning Environment Design, or in attending my online Learning Ecosystems course, coming up in the Guild Academy beginning September 9. Or plan to attend the blended version of the course in advance of the Learning Solutions conference in Orlando in March of 2015.

* You can access information about the 2014 Corporate Executive Board study by downloading the 3Q Learning Quarterly, or checking out these blog posts:

> Three Shifts Every Company Should Make to Shape its Learning Culture

> More Learning Through Less Learning: Reframing Learning Culture.

Of course, if you are lucky enough to have CEB membership, you can get a copy of the entire study.

Posted in Learning Environment Design | 4 Comments »

This post is the first in an occasional series in which I will share my book recommendations on a variety of topics. Stephen King has said, “when you stack up the years we are allowed against all there is to read, time is very short indeed.” In these Bibliophile’s Bookshelf posts, I’ll be offering a short list of books for people with limited time – books that I think get to the heart of the matter and offer great advice. Enjoy!

ON CONSULTING

The role of a consultant varies widely, and the competencies necessary to be effective also constitute a long list. Learning to be an effective consultant requires gaining expertise, strategizing a process that works, becoming skilled at data gathering and analysis, developing a wide range of communication and influence skills, and more. Of course, having one’s own consulting practice requires yet another set of skills in business development and marketing – but that’s a subject for another post. For now, here are my picks for consulting books to have on your bookshelf, whether physical or virtual.

Consulting in Uncertainty: The power of inquiry

Ann K. Brooks and Kathy Edwards

Routledge, 2014. On Amazon here.

This book takes a unique – and thoroughly modern – look at consulting as an action learning project instead of as an advice-giving enterprise. Brooks and Edwards suggest that the best outcomes will come from a collaboration between consultants and clients with each bringing their areas of expertise to the table and engaging together to define questions and seek answers. They also advocate experimentation along the way – testing theories and validating approaches before going all-in on a particular response to an organizational opportunity or issue. Consulting in Uncertainty is a small book, but it covers all the bases: a consulting model (the inquiry model), methods, needed skills, and consulting challenges.

“Consulting as inquiry assumes that (a) consulting must be outcome oriented rather than problem oriented; (b) consulting must be focused on the co-creation of new knowledge rather than expert knowledge; (c) consulting and client relationships are personal rather than just professional; and (d) dynamic rather than static knowledge is needed in a diverse and uncertain world.”

~ Ann K. Brooks and Kathy Edwards, Consulting in Uncertainty

The Trusted Advisor

David H. Maister, Charles H. Green, and Robert M. Galford

Touchstone, 2000. On Amazon here.

And:

The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook: A comprehensive toolkit for leading with trust

Charles H. Green and Andrea P. Howe

John Wiley & Sons, 2012. On Amazon here.

The Trusted Advisor provides practical advice on building trusting relationships with clients – the kinds of relationships in which you can truly be a valued collaborator, sought-after advisor, and business partner. Maister, Green and Galford do a great job laying out different levels of relationships (service-based, needs-based, relationship-based, and trust-based) and readers can imagine when each level might be appropriate. If you want to reach the trusted advisor level, the book offers a trust equation and a trust development process that provide guidance on how to engage with clients to build deeper relationships. There is also plenty of advice on practical skills. The Trusted Advisor Fieldbook supplements these ideas with helpful checklists and spotlights on specific aspects of consulting engagements (e.g. pitching ideas, managing risk, communicating at the C-suite level).

“While outstanding technical competence (or content) is a nonnegotiable, essential ingredient for success, it is not sufficient. Trust is a lot richer than logic alone, and it is a significant component of success.”

~ Charles H. Green and Andrea P. Howe, The Trusted Advisor

Consulting on the Inside: A practical guide for internal consultants

Beverly Scott and B. Kim Barnes

ASTD, 2011 (2nd Edition). On Amazon here.

Many people who work in learning and development roles are employees of the organizations they support – that is, they consult from the inside. Scott and Barnes’ book speaks to the dynamics of that particular role, and readers will recognize the joys and the challenges inherent therein. This book offers a take on the consulting process that is more traditional, although Scott and Barnes take pains to point out that it is an iterative and complex one. There is solid advice on all of the typical process activities – contracting, gathering data and giving clients feedback, strategizing change, implementing, and evaluating. You’ll also find several chapters dedicated to exploring the skills needed to be effective. In addition, Consulting on the Inside is very readable, with many sidebars, bulleted lists, and summaries.

“Becoming a master consultant is the result of a long journey. No matter how well educated or intelligent you may be, mastery is not given, but rather earned through courageous action, thoughtful reflection, and the discipline of learning from both success and failure.”

~ Beverly Scott and Kim Barnes, Consulting on the Inside

Additional books on the topic of consulting abound, and I welcome suggestions as to your favorites if you want to comment below. Nearby on the same bookshelf are books on consulting as a business, performance consulting, and assessing needs. But those are posts for another day.

Posted in Bibliophile's Bookshelf, Book Discussions | Leave a Comment »

I read some really interesting work from one of my favorite authors over the weekend. Brandon Sanderson, who writes amazing fantasy novels and stories, just published an anthology with three colleagues that demonstrates how they supported one another in developing a set of short stories. The book is called Shadows Beneath: The Writing Excuses Anthology, and in addition to the final piece, the anthology contains transcripts from brainstorming and critique sessions as well as “track changes” documents that show the differences between the first draft and final version.

From what I’ve seen, many novelists have strong writing groups that they rely on as first readers and candid critics for draft material; the writing groups point out flaws and help authors think through writers block. They help each other to learn the craft. Brandon Sanderson has said that he has a reliable group of fellow authors and prime readers who know his writing, his characters, and his complex world-building as well as he does, and they help him shape his work. The involvement of this group doesn’t diminish Brandon’s brilliance, or make his novels co-authored works.

Reading Shadows Beneath got me wishing intently that we did more of that kind of workshopping in our own field. Even in organizations that have large learning and development teams, I haven’t often heard of practices that include regular sharing of works-in-progress. And it can be very difficult to get deep reviews and critiques when you are relatively independent in your work.

The idea of workshopping our work is in alignment with the “working out loud” mantra (see Jane Bozarth’s Show Your Work) and advice offered by Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace in Creativity, Inc. (longer discussions of each forthcoming).

Working out loud (often by posting about projects in social venues) gives others the opportunity to support our work and opens the door to collaboration on areas of mutual interest. Just as importantly, it exposes the thought process – the why of work – so that others may learn from (or influence) that as well.

In Creativity, Inc., Ed Catmull shares the “brain trust” practice at Pixar where emerging material is screened and discussed at length, often dramatically changing films from original concept to final project. These discussions are not seen as “slowing down” the process or as interfering with a director’s creative vision, but they are largely responsible for the exceptional quality and innovation of Pixar’s products.

The value of this kind of critique is well-known. Back in 1987, Donald Schon advocated for a practicum approach to teaching professional practice in Educating the Reflective Practitioner:

“Perhaps, then, learning all forms of professional artistry depends, at least in part, on conditions similar to those created in the studios and conservatories: freedom to learn by doing in a setting relatively low in risk, with access to coaches who initiate students into the “traditions of the calling” and help them, by “the right kind of telling” to see on their own behalf and in their own way what they need most to see” (p. 17).

Schon’s advice might be directed at those who teach graduate programs in our field, but Ed Catmull shows us that the same kind of environment can be created in the workplace. In truth, we need both – our graduate programs often need more embedded practice and critique, and our workplaces need to have safe avenues for collaborative creative discussions.

While we might agree a workshopping process would be beneficial, there are actually a lot of headwinds. Most professionals in our field are rewarded for their individual efforts, and are working in environments characterized by tight deadlines and scant resources. Graduate courses educate people with a wide range of backgrounds and practice areas in the same course, so defining projects and scoping them within the confines of a term can be tricky.

I can see the barriers that need to be overcome in my own work… the fact that I have a solo consulting practice, the particulars around some of my course design work, and the time constraints I am under (and that potential collaborators are under as well).

Nonetheless, it’s worth considering how we might workshop our designs and our writings more often and more thoroughly. The practice would support the development of professionals in our field , improve the quality of our outcomes, and accelerate adoption of new techniques and tools. I’d love to hear how you find ways to workshop your work.

We can do more, I think, to help each other learn our craft.

Posted in Article Discussions, Reflections | Leave a Comment »

The last set of readings in my emerging technology class was on the “maker movement.” The Horizon Report subtitled that as “shift from students and consumers to students as creators.” Those of us in learning and development are usually appreciative of ways to engender active, hands-on learning, so “making” is a trend we should watch.

Online, we had a lot of discussion about whether people who created intellectual products (e.g. writing, plans, designs) were included as “makers,” and we discussed whether we had to see “making” as usually about new ways to make money. I liked Hagel, Brown & Kulasooriya’s definition of maker as “someone who derives identity and meaning from the act of creation.” I can tell you that I certainly feel that way about all the slide decks I create!

There is a lot of interesting material on this trend – enjoy these readings. And please share other references if you like.

If you’ve been following along, this post is the final one in a series which reading lists for the overview of emerging technologies, social media, MOOCs, and learning analytics. Thanks for following along.

Introduction

When you first start looking into the “maker movement,” you might think that it is especially important for modern day entrepreneurs and not necessarily of interest to corporate learning and development strategists. But the movement at its core is about the freedom to create, and from a learning perspective, the depths of learning that comes out of that creation. (See the Maker Manifesto, under recommended readings, and notice that making, learning, and playing go hand-in-hand.)

There is a lot of discussion about “making” in the education arena, and it will, I think, eventually come to the T&D space as well. Corporations already try to encourage innovation by giving employees a chunk of time to do their own projects – they know that the employees will come up with great ideas that the company might never have developed otherwise.

The constructivist and constructionist learning theories would strongly endorse this approach, and some of your readings dig into those theories a bit more deeply. I would encourage you to pull out your adult learning texts and remind yourself of constructivist theories as a way of understanding how learners as creators makes a great deal of sense.

In T&D, we should look at how making can be an important learning and teaching technique – and consider what hands-on projects might really help our learners to more fully understand key concepts and approaches. Some of our existing techniques, like problem-based-learning, action learning, and other “hands on” strategies fall in alignment with the spirit of “making” I think. But I’ll be interested to hear how you see it.

Required

A Movement in the Making. By John Hagel, John Seely Brown, & Deleesha Kulasooriya. (Deloitte University Press, 2014)

What Is the Maker Movement and Why Should You Care? By Brit Morin (Huffington Post, May 2, 2013)

What’s the Maker Movement and Why Should I Care? By Gary Stager (Scholastic Web Site, Winter 2014)

The Maker Movement and the Rebirth of Constructionism. By Jonan Donaldson. (Hybrid Pedagogy, January 23, 2014)

How the Maker Movement is Transforming Education. By Sylvia Libow Martinez and Gary S. Stager. (We Are Teachers web site, nd). See also the links provided to the left of the article.

Recommended

What We’re Reading. (Making Things Happen, Agency by Design project, Harvard Graduate School of Education) This post lists quick reviews of a variety of books on the subject of “making” – great for bibliophiles! The Agency by Design web site is worth exploring.

The Maker Movement Manifesto. (Sample chapter PDF available here) By Mark Hatch.

A Defense of Constructionism: Philosophy as conceptual engineering. By Luciano Flroidi (Metaphilosophy, 2011) Available through Penn State’s databases – Wiley Online Journal Library.

Mapping Digital Makers: A review exploring everyday creativity, learning lives and the digital. (PDF) By Julian Sefton-Green

Learning Creative Learning (MOOC-like course). By MIT Media Lab and P2PU, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. March-May 2014, materials still available.

Posted in Trends | Leave a Comment »